When you look up a word in the dictionary, do you end up spending half an hour looking up twenty other words? Psychologists have a clinical term for this. You could look it up.

If you forage for words in dictionaries, here’s a little vade mecum you should have while you endure a long telephone hold with smarmy “Your call is very important to us” white lies and Kenny G looping.

It’s just six pages long and printed small enough to fit in your pocket. The little dictionary’s 32-word title is almost bigger than the book. I’ll shorten it to the Chinook Jargon Pocket Dictionary.

Nard Jones, a long-time editor at the P-I, overheard phone conversations among Seattle old-timers in the 1950s like this: “Kloshe, Arctic Club, twelve o’clock. Alki, tillikum.” Translated into everyday Clavipeninsular English, “Fine. Artic Club, twelve o’clock. Later, pal.” The old fellow was confirming a lunch date in Chinook Jargon.

By the time Jones wrote “The Lost Language of Seattle” in the 1970s, the old Gold Rush boys were gone and with them nostalgia for the Chinook Jargon they used in those days of yore in the Yukon.

The elderly ex-prospectors were some of the last to keep alive the trade language that had been used up and down the Pacific Coast by French-speaking voyageurs, English-speaking traders, and Native Americans throughout the 1800s. During the Gold Rush of the 1890s there were 100,000 gold hunters and indigenous peoples speaking it.

Chinook Jargon is technically a pidgin. Professors of linguistics use the term pidgin to refer to a grammatically simplified, blended language used by people who need to communicate but do not share a common language. There have been hundreds of now extinct pidgins spoken by European traders and their buyers and sellers in Asia, Africa, and the Americas. Mobilian pidgin, for example, was used for 300 years by hundreds of tribes and dealing with Europeans along the Gulf Coast. Its last speaker died in 1950.

The now almost extinct Northwest trade language was developed to solve the business problem faced by Hudson Bay Company traders, who spoke French and English, and by indigenous traders of mutually unintelligible Native American languages.

When the Wilkes Expedition explored the South Sound in the 1840s and built a base just south of present-day Steilacoom, American explorers learned the local lingua franca from their guides and food suppliers among the Nisqually and the Squaxins. A 20-year-old polyglot genius, Horatio Hale, a brilliant Harvard dropout like Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg, came west as the Expedition’s philologist. Hale mastered what his informants called “Chinook Wawa” in an afternoon. His tour de force report on the dozens of languages he studied on the Expedition was published in 1846 with a long chapter on Chinook Jargon. While Captain Wilkes was mapping the South Sound and naming waterways after Expedition members, he honored young Hale with nearby Hale Passage.

The Chinook Jargon Pocket Dictionary was printed for prospectors heading for the Yukon. Surviving copies are occasionally listed for sale in auctions, and collectors bid hundreds of dollars for them. The rest of us access the book online where the scanned copy from the University of Alberta library is well known to all the usual search engines.

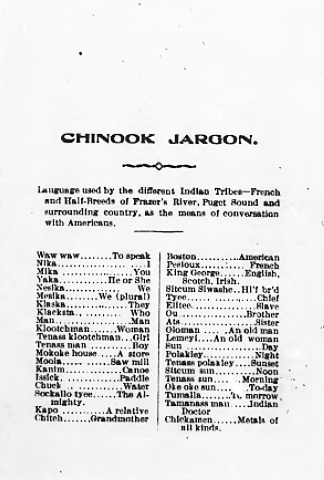

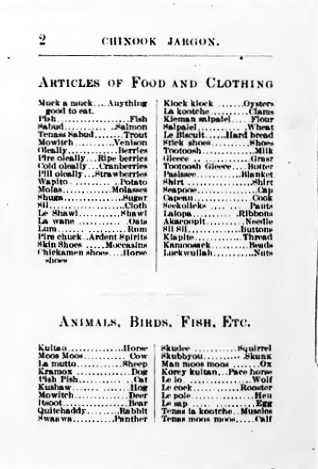

When you peruse the little dictionary in an idle moment, you’ll discover you’ve been using Chinook Jargon all along. A self-important person is a “high muckety-muck” and a good-for-nothing, “cultus.” A sturdy structure is “skookum, right?” I remember affectionately my father-in-law George Lund using all three expressions.

You’ll discover nearby place names based on words in the little dictionary. Just for a start: Alki “sooner or later,” Hyak “swift,” Kopachuk “waterfront,” Olalla “berries,” Skookumchuck “strong waters,” Tukwila “hazelnut,” and Tumwater “booming water.”

The venerable watering hole in Gig Harbor called the HI-IU-HEE-HEE, is pure Chinook Jargon, “hiyu “plenty” and “heehee “fun.” The state ferries Tillikum “friend” and Kaleetan “arrow” are still in service, while the Klahoywa “hello,” Kalakala “bird,” and Illahee “land’ are long gone.

High school girls in Western Washington invite boys to Tolo dances —or at least they did before COVID-19. Tolo is the jargon word for “success,” but I’ll let you explore that word story on your own.

Long before Seafair, Seattle’s annual civic festival was The Golden Potlatch. The word potlatch is pure Chinook Jargon. Borrowed from the Nootka verb for “give,” potlatch became the word for the wide-spread Native American ceremony of gift-giving and ritual feasting.

Enjoy looking through the Chinook Jargon Pocket Dictionary’s list of 292 words. You’ll be surprised by the words you recognize.

At the end of his life, Horatio Hale, when turn-of-the-century idealists in Europe hoped a new international language would bring peace to people separated by their languages, called Chinook Jargon a worthy precursor of Volapük and Esperanto.

One hundred and thirty years later and once again there are tribes of people in America who do not share a common language.

Maybe it’s time to work out a new pidgin like Chinook Jargon to talk to each other.

Kopet wawa. Mamook kwollan. Literally, “Stop words. Do ear.”

Be quiet and listen.

Now that’s an aspirational motto for 2020.

SIDEBARS

Chinook Jargon is not just rich in toponyms, but also in eponyms. A Boston is an American, and a King George is Canadian or English. The adjective pelton means “crazy” and refers to poor Archibald Pelton, a trader who was well known for succumbing to insanity at old Fort Vancouver in the 1840s.

____________________________

The beginning of the Our Father translated by the Methodist missionary Myron Eels, one of the great authorities on Chinook Jargo:

Nesika Papa klaksta mitlite kopa saghalie, kloshe mike nem kopa konoway kah. Kloshe spose mika chaco delate tyee kopa konoway tillikums.

Our Father who lives in heaven, good is your name everywhere. Good if you become true chief over all people.