One Tuesday afternoon in February 1920 A. H. Miller, Special Agent of the United States Department of Justice at the Laredo station, received this urgent telegram from San Antonio:

Press reports indicate Johnson will leave Mexico City Thursday this week on route United States. Am today in receipt following wire from Chief: “Johnson should be taken into custody as fugitive from Justice immediately on entering United States territory. When he is arrested notify this Bureau and its Chicago office.”

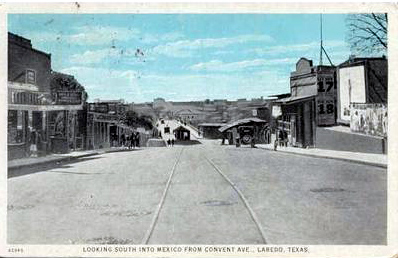

Miller replied to his chief at the Bureau of Investigation in Chicago the next day reporting that his deputy “was reliably informed that JOHNSON was en route to Laredo, accompanied by his Attorney,” along with details of preparations there for arresting the fugitive at the Immigration Station on Thursday.

The arrest at the bridge planned for February 26, 1920 never happened.

Johnson never showed up.

But the story had legs, and the Laredo Weekly News ran an article on the 29th (1920 was a Leap Year) with the headline, “JOHNSON WILL ARRIVE IN NUEVO LAREDO TOMORROW.”

Why all the excitement about a fugitive named Johnson returning from Mexico?

Who was this guy?

Well, only the most famous boxer in the world!

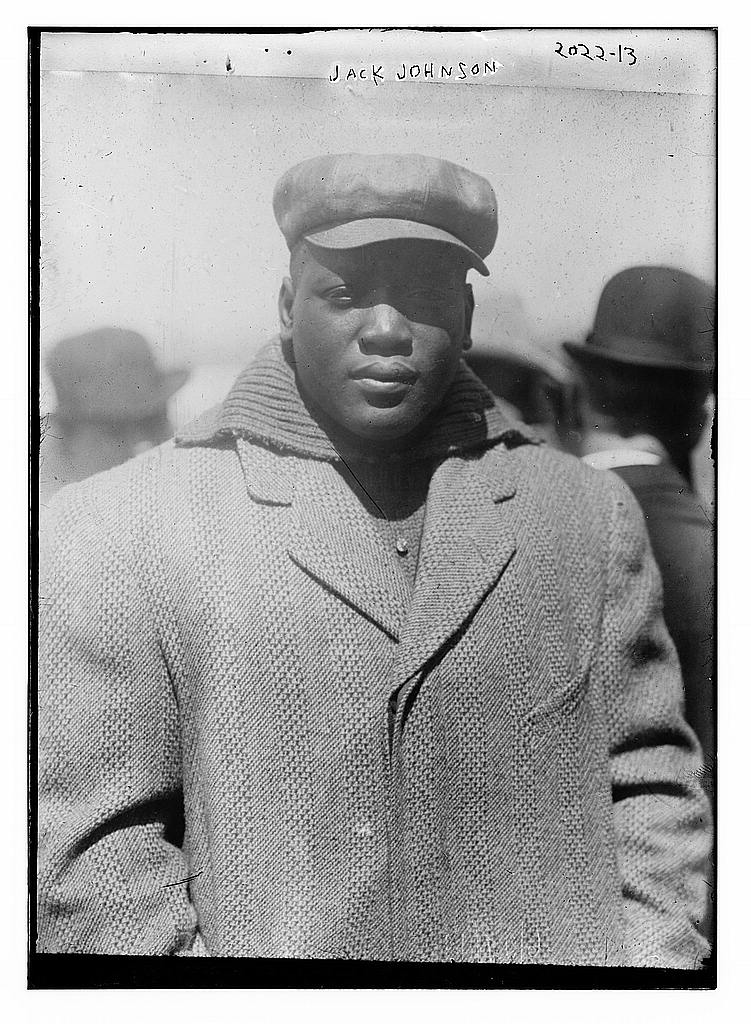

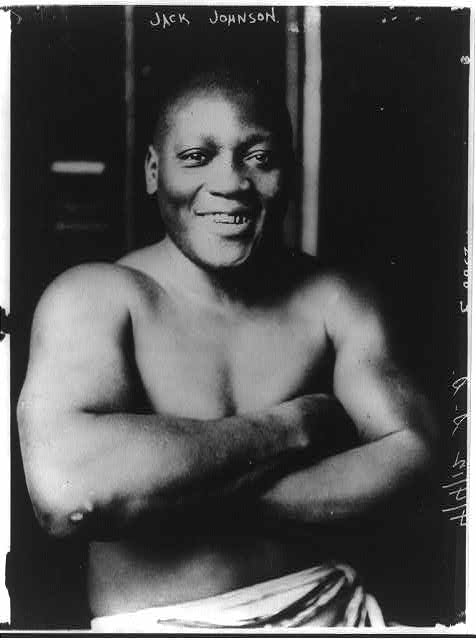

The fugitive was Jack Johnson, The Galveston Giant, the first African American World Heavyweight Boxing Champion.

Johnson held his title from 1908 to 1915, seven years of defeating all the “Great White Hope” challengers in bouts that mesmerized white and black Americans — but for opposite reasons. Johnson’s 1910 title defense on the Fourth of July against the white challenger Jim Jeffries in Reno was billed as “The Fight of the Century.” Twenty thousand white boxing aficionados arrived on special trains to see the fight in Reno, most of them hoping to watch the black champion humiliated.

The prizefight, scheduled on a national holiday to attract the largest possible audience as well as for the symbolism of the event, was much more than a boxing match. It was a contest of racial supremacy, white vs. black, and the entire nation viewed it that way. The Chicago Defender, a newspaper written by African Americans for African American readers, offered this opinion, “on the arid plains of the Sage Brush State, the white man and the Negro will settle the mooted question of supremacy.” The mere presence of Johnson in the same ring with a white opponent had been called by another newspaper “a national disgrace.” To which a black editorialist gave a witty riposte predicting Johnson would knock out Jeffries “just to make it a good national disgrace.”

Emotions were high on both sides of the Color Line. One Southern official vented, “Why, some of these young negroes are now so proud that it is hard to get along with them, but if Jeffries should be beaten by Johnson they will be crowding white women off the sidewalks.” The Apocalypse, in other words.

The “Fight of the Century” had always been about a far more violent fight than boxing.

On the day of the match in far-off Reno, white fans of Jeffries and Johnson’s black supporters across the country gathered in segregated, partisan crowds at local Western Union offices to hear the minute-by-minute, blow-by-blow accounts of the fight read from the telegraph’s ticker tapes.

Jeffries was no match for Johnson. By the 14th round his white face was bloody, he had a broken nose, and his eyes were swollen shut. In the 15th round he was staggering around the ring blind and half-conscious. His trainers threw in the white towel acknowledging defeat. Even the trainers in Jeffries’ corner were worried about the inevitable riot should Johnson win by a knockout. There was anger among the disappointed whites and jubilation in the African American community.

The next day, an African American poet, William Waring Cuney, wrote an epic poem praising Johnson’s heroic victory. It began with this verse:

O my Lord

What a morning,

O my Lord,

What a feeling,

When Jack Johnson

Turned Jim Jeffries’

Snow-white face

to the ceiling.

The celebrations in black neighborhoods, however, quickly turned to terror as white gangs rioted and attacked African Americans on the streets. In the week after Johnson’s triumph over that latest “Great White Hope” race riots broke out in New York, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, New Orleans, Atlanta, St. Louis, Little Rock, Houston, and dozens of other cities. White mobs murdered at least 20 blacks and injured hundreds more.

Jack Johnson was both famous and infamous, and he was hated with the same intensity that he was adored.

That’s why, if Johnson had arrived as predicted and the arrest been made, Agent Miller and Laredo would have been on the front pages of every newspaper in America.

For comparison, imagine that Muhammad Ali had fled to Mexico in 1966 after being convicted of draft evasion, instead of staying in the US to fight the case all the way to the Supreme Court. Then imagine the FBI agent in Laredo getting a phone call from J. Edgar Hoover telling him to expect Muhammad Ali, the convicted fugitive boxer, to cross the International Bridge two days later. All the TV networks and every newspaper in the Free World would have had live remote crews and reporters at the foot of Convent Avenue, pushing and elbowing their way toward the Customs and Immigration station for a better view of the arrest.

Media spectacles in 1920 didn’t make nearly the splash they do now. There was as yet no TV, little radio, and no Internet —not even La Gordiloca! Had Jack Johnson surrendered to Agent Miller that day, it would have been the biggest news story in Laredo’s 300-year history.

But Johnson changed plans, and his February 1920 arrest is one of the greatest Laredo stories… that never happened.

As with Muhammad Ali 50 years later, the American public’s fascination with Jack Johnson involved a charismatic African American athlete, race relations, the law, and politics.

Like Muhammad Ali, Johnson refused to conform to the stereotype of the happy-go-lucky, subservient African American man. Both boxers were witty in speech and bold in their plain speaking. Neither backed down when insulted. Muhammad Ali bragged in rhymes and spoke out against the Vietnam War. During fights Johnson grinned as he exchanged taunts with ringside racists. While he was in Spain during World War I he got a reputation for being a paid agent of Germany when he said that he had been mistreated by America, England, and France, but that “In Germany I’m treated like a man, and my wife like a lady.”

Johnson’s legal troubles came with passage of the 1910 Mann Act, unambiguously known as the “White Slave Traffic Act.” It was a statute enacted to calm fears that the flood of immigrants not from Northern European Protestant countries were capturing farm girls and innocent maidens, forcing them into prostitution in the new big cities. The statute had ostensibly made it illegal to transport across state lines “any woman or girl for the purpose of prostitution or debauchery.” In fact, it was the law’s ill-defined, open-ended next clause, “for any other immoral purpose,” that was generally invoked by law enforcement as a carte blanche for arresting any man who traveled across states with an unmarried woman. Especially African American men, as Chuck Berry was to discover in 1962.

It was one thing for white people, especially those in the Jim Crow South, to see a black fighter defeat white boxers. It was hard enough for that resentful group to tolerate seeing Jack Johnson sharing the same ring with his white challengers. But his notorious success in another, more private space with a long series of white floozies, prostitutes, camp followers, and what in the 70s were called “groupies,” drove a certain sector of men wild with indignation and revulsion. Their conscious racism and subconscious horror of miscegenation meant that the Color Line was drawn most prominently at the bedroom door of white women.

In that environment it was inevitable that Jack Johnson would be charged and tried under the Mann Act. When he took his white fiancée Lucille Cameron as a companion on a train trip from Chicago to Pittsburgh, he was. Nevertheless, Cameron, who later married Johnson, refused to cooperate with the prosecution and the case was dropped. Several months later he was charged again for the same ‘crime’ with another white woman. This time it was for travelling across state lines with a certain Belle Schreiber, who actually was a prostitute. Schreiber and Johnson were ‘very well acquainted,’ and for a substantial bribe, the venal Belle took the stand as the prosecution’s main witness. With her lurid testimony, the reigning Heavyweight Champion of the World was convicted and sentenced to a year and a day in federal prison.

However, before beginning his jail time, Johnson escaped to Canada by train, hiding among players on a touring Negro National League baseball exhibition team. He threw on a team jersey just as the train pulled in to the station at the Canadian border. Federal officers boarded the segregated black passenger coaches on the lookout for him and even had a mug-shot photograph. They missed him, however, because, as they explained, they “couldn’t tell one n _ _ _ _ _ from another.”

Johnson tells this story in his posthumously published autobiography, Jack Johnson Is a Dandy. His recent biographers can’t decide whether it is true or just good storytelling.

The convicted boxer spent the next seven years abroad, a fugitive from justice. During his peripatetic, hotel-hopping lifestyle across Europe, the Caribbean, and ultimately Mexico, he was never absent long from newspaper headlines. There were cleverly publicized boxing matches and exhibitions on the sports pages. Johnson was always a great interview, good for outrageous remarks. Glamorous photos of the mixed-race married couple in expensive clothes on luxury liner gangplanks scandalized and titillated some and wowed others in separate but unequal American audiences.

By 1920 Johnson was weary of the exile’s life, and the income from boxing pseudo-fights and exhibitions had never been enough to feed the bonfire of his cash’s burn rate. He missed America and the easy money there. He had convinced himself that the sentence for violating the Mann Act might be commuted, or that if he returned to the U.S. voluntarily, he would be granted clemency and not have to serve any jail time.

So, in the summer of 1920, Jack Johnson moved to Tijuana, where he opened a saloon and named it “The Main Event Café,” a TV-less precursor of the modern sports bar. A month later, ready to surrender, he held out his hands for the US Marshal’s handcuffs as he crossed the border line at San Ysidro south of San Diego.

It was July 20, 1920, four and a half months after his no-show in Nuevo Laredo.

The voluntary return to the US earned him no clemency, and Johnson served every day of his year-and-a-day sentence in a Kansas penitentiary.

He died in obscurity in a one-car North Carolina car wreck. It was 1946, long after his decades of fame, when he had been the most famous African American athlete in the world.

His pardon had to wait until May 24, 2018.

President Trump, at the behest of a rich fool who’d made a fortune acting in boxing movies, pardoned Johnson in a cynical publicity-stunt 98 years after his arrest on the California border.

…

But hang on! Jack Johnson did come to Nuevo Laredo.

It wasn’t in February 1920, but in August the year before.

Watch for the forthcoming soon Part II of this chronicle in LareDOS to find out what really happened when Jack Johnson was in Nuevo Laredo.

Sources:

Laredo Weekly Times, February 29, 1920

Randy Roberts, Papa Jack: Jack Johnson and the Era of White Hopes (1983)

Ken Burns, Unforgivable Blackness: The Rise and Fall of Jack Johnson (PBS, 2005)

Geoffrey C. Ward, Unforgivable Blackness: The Rise and Fall of Jack Johnson (2006)

Theresa Runstedtler, Jack Johnson, Rebel Sojourner Boxing in the Shadow of the Global Color Line (2013)

Facsimiles of Johnson’s FBI files are online at: http://www.pbs.org/unforgivableblackness/knockout/fbifile.html