It happens as I turn off U.S. 83 and drive northeast onto Ranch Road 3169 — anticipation morphs into a sense of well-being. I’m four minutes from paradise and the welcoming clank of padlock and chain at the front gate that opens to “el pie del rancho,” the houses, bodegas, and the corrales.

I like to think that my grandparents, great grandparents, and aunts and uncles experienced this place as I do with love and reverence for its tranquility. natural beauty, and family history.

It is very early morning. I’ve prepared what we need for a roundup — extra feed, ear tags, medicine and syringes, and lunch.

The day will unfold in sounds, colors, and textures that have been etched on this heart since childhood — the familiar pleasures of the sight of what is in bloom, the graceful gray agaves with their slender flower spikes that have shot 20 feet into the air, the bright green bonnets of the mesquites.

This is where my writer’s heart lives and takes sustenance. This is where I lived for many of the 20 years that I wrote and published the hard copy version of LareDOS.

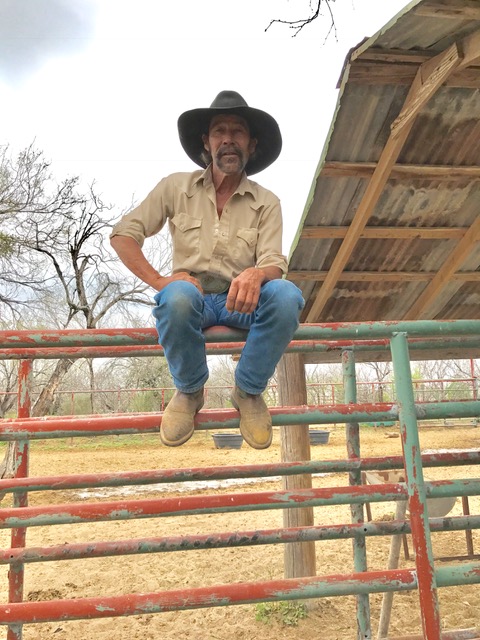

Though the day’s agenda is rounding up cattle, far more will transpire. There will be vueltas down every sendero to cajole errant bovines into the dominion of the corrals. There will be dust and mesquite smoke as the branding irons heat up, and surefooted men move cattle into the pens. There will be good conversation over a campfire meal and some exaggerated storytelling. There won’t be any beer. That doesn’t happen here while we move thousand-pound beeves.

By mid-afternoon, the work is done. The tools are put away, the fire doused, and the scuffed-booted cowboys drive off in their pickups to Zapata and San Ygnacio.

The noise has died down, save for the plaintive Wish You Were Here telegraph of mother cows bellowing over the separation from bawling calves. I‘ve sent that telegraph myself more than once. It’s what mothers do.

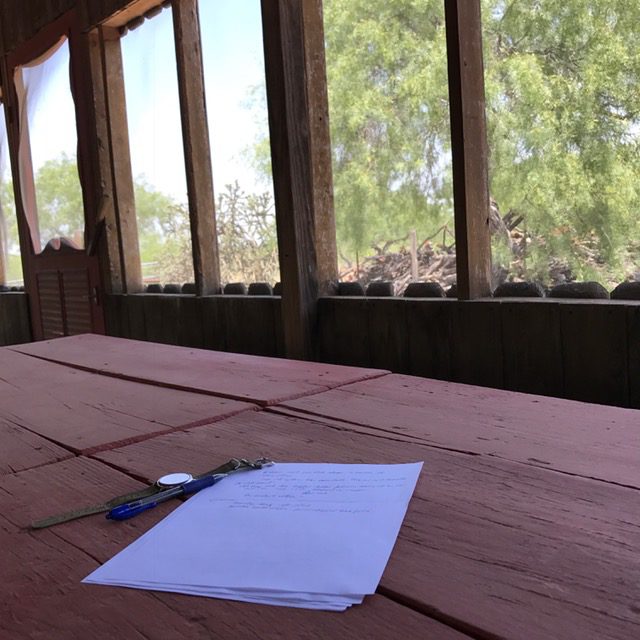

I retreat to the screened-in casita, the cooking house, to sit at one of the rough hewn plank tables that were in my grandmother’s ranch house. How well we remember that we loved sitting there with her, a hearth fire in winter warming the kitchen.

There was a way night fell when we were with her at the ranch, siblings and cousins lined up on canvas cots. I remember the breathless Rosary she prayed so quickly as though to ward off some pending travail, the fragrance of rosewater, the dimming of the kerosene lantern, the silence of the wild world beyond the thin board and batten walls of the small ranch house, and before sweet dreams the last look out the window at bright stars on a nightscape of zero ambient light.

This long day moves to its completion, and a myriad of gifts present themselves — vermillion fly catchers, a huge Gecko navigating across screen wire, butterflies, birdcalls, and the precious sighting of a red fox that moved in playful leaps from the pond up to my house.

It is at that weathered table that I take stock of the day and this life, and I remember that not long ago when I was intrepid and agile I worked cattle in the pens in the thick of it all, a woman with only a stick between her and the hooved behemoths.

As was the case during my grandmother’s earthly tenure, life-changing events have redefined my work on the ranch. She lost her sight.

Me? I’ve been relegated to the planner of the work here, an advisor and front-row observer of roundups, sometimes the fire builder and the cook.

Even so, I wouldn’t miss one.

To love the land and the domestic and wild things that make it their home is to acknowledge and love God.