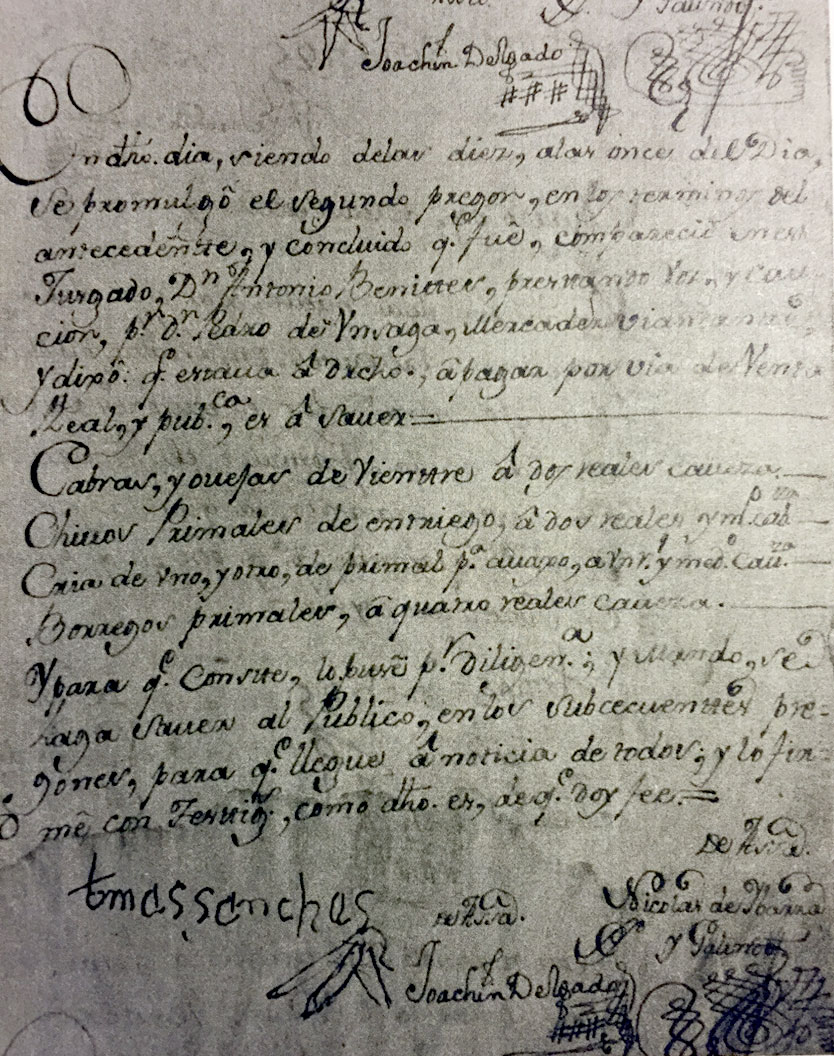

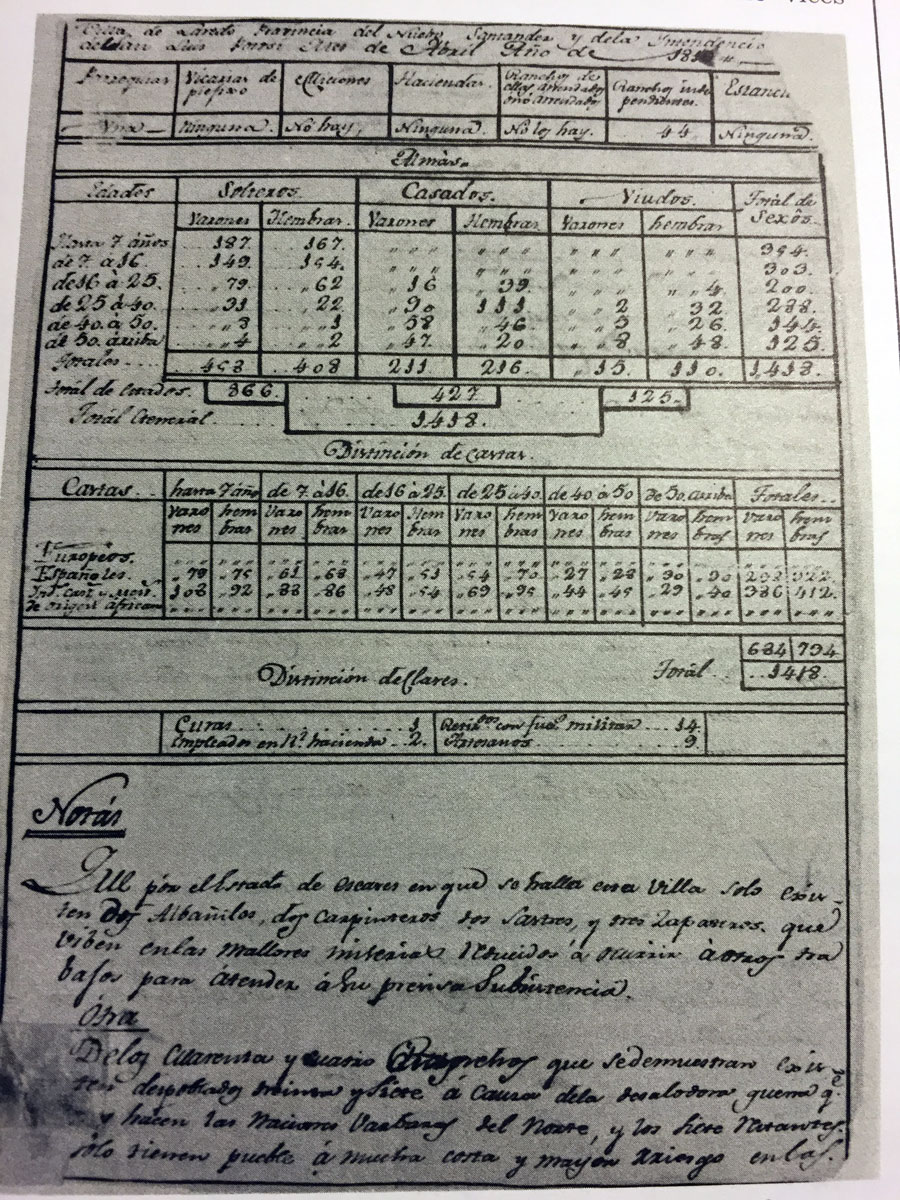

(Photos of documents from the St. Mary’s University Spanish Archives of Laredo, provided by the author.)

In the Laredo Archives, Box 8, Folder 13, there are 44 typewritten pages in Spanish pertaining to a murder/suicide mystery that occurred on Saturday, July 30, 1768 — a copy of the original report made the following day by Joseph Martínez de Sotomayor, Captain and Supreme Magistrate of the Villa de San Agustín de Laredo.

Capitan Sotomayor had heard from Don Xavier de Uribe that María García, the wife of Félix Básquez, a servant in his household, was found hanging inside her jacal around three o’clock in the afternoon. She was found next to the edge of the bed.

Captain de Sotomayor went to the jacal to investigate and found two witnesses — her loving son and her husband. There were a few curious neighbors who also were outside the jacal. With the use of a knife, the captain cut the rope and ordered that the body be taken to San Agustín Plaza.

The husband and their eighteen or twenty-year-old son and seven persons who knew members of the household accompanied the body.

At San Agustín Plaza, Captain Sotomayor was to conduct an inquiry to determine, if indeed, María García died from a homicide or if she had lost her five senses as a result of an accident and committed suicide.

Afterwards, the captain was going to turn the body over to Father Nicolás Gutiérrez de Mendoza, for proper burial in the parish of said Villa. The captain had twenty to twenty-four hours to conduct the inquiry before burying the body. He was afraid the body would become bloated and explode and this would not be sanitary for the neighborhood.

While the body lay face up on the ground of San Agustín Plaza, the family of Don Xavier de Uribe was also present.

The captain knelt next to the body and placing his ear near her mouth, he asked in a loud voice, “In the name of God and the Blessed Mother, María García, talk to me and tell me who murdered you? Who hung you? Who incited you to do it? If you did it because you were desperate and without fear of Divine Justice and without respect for the King, or if you did it because you were deprived of your senses because of high fever, dementia, or disinclined, I order you to speak.”

As he was uttering these words, the captain carefully watched the surrounding crowd for any signs like facial expressions, eye contact, or nervousness that would indicate who the guilty party was.

In due time, the dead person did not speak, nor did the live ones make any signs of malicious guilt. The captain questioned various members of the Uribe family and took them as prisoners until such time that he could verify their statements. The captain/magistrate summoned Joseph Félix Básquez, the husband of the deceased, to his court, along with the other witnesses. Básquez made the sign of the cross and took an oath to tell the truth and nothing but the truth, knowing full well that perjury to a Christian would cause harm to his soul and corporal punishment to his body. The captain/magistrate asked Básquez if he knew the deceased María García, and he answered in the affirmative, stating that she was his wife and they lived in the Hacienda del Alamo de Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe, in the jurisdiction of the Real de Santiago de Sabinas, in the Nuevo Reyno de León.

The captain/magistrate asked Joseph Félix Básquez if during their marriage they had any disagreements over the deceased wife being a widow or over the rearing of their seven children. The response was that he did not have any disagreements. He was then asked if there was any jealousy on either party that might have caused a public scandal. The response was in the negative, that neither in his youth nor in old age. He did talk to other women but he never gave her sufficient motives, in public or in private, and any slight reproaches stayed between husband and wife.

He was asked if during their marriage, she had suffered a serious sickness that could have affected her senses and caused dementia. He said she did have a stomachache for two years until her death. According to his testimony, the husband of the deceased and her son were in the corral with the horses when they were notified of the tragic death. An adopted orphan girl of the deceased and another girl, María Gonzáles, the daughter of Doña Francisca de Uribe, were playing in the deceased’s jacal when María García chased them away. María Gonzáles noticed that she was holding a rope in her hand and asked her why she had a rope.

The mother of the orphan girl asked her to leave and after the girl was alone in the house, María García beat her with a stick and chased her away. After a long while, the orphan girl returned to the house, and upon finding her mother hanging, she ran out of the jacal hysterically shouting that her mother had hung herself.

All the facts, however, seem to point to suicide since the woman had been known to suffer from pains, and perhaps, mental illness.

SIDEBAR

How I came to know the existence of The Spanish Archives of Laredo

While I was growing up in El Barrio Azteca in Laredo and having lived in my hometown until 1967 when I transferred as a junior from Laredo Junior College to St. Mary’s University in San Antonio, I had never heard of these very important historical documents called the Spanish Archives of Laredo.

I was ignorant of their existence; it was never mentioned in my formative years attending St. Augustine School or while taking Texas history at the college.

And none of my peers mentioned the Spanish Archives of Laredo. I can only surmise that they did not know either.

Towards the end of my junior year at St. Mary’s, I noticed a part-time job opening for a bilingual student assistant that was posted on the huge glass-encased bulletin board between the administration building and Reinbolt Hall.

I applied and went for an interview with Miss Carmen Perry, archivist of the Spanish Archives of Laredo. Her office was on the third floor of the Academic Library, now the Louis J. Blume Library in the Special Collections Room.

At the beginning of the interview when she first mentioned the Spanish Archives of Laredo, I was flabbergasted. I did not know that my hometown had such a rich Spanish history. She also told me that she was hired a few months before and that she was looking for a student who was fluent in reading and writing Spanish and who could be her assistant.

Miss Perry was a native of Torreón, Coahuila, Mexico, and was a fluent in reader and writer of Spanish. Her previous work assignment was head librarian at the Daughters of the Republic of Texas Library at the Alamo.

The task, she said, was to translate, catalogue, and index this valuable collection. Miss Perry wanted an index card for each document — a painstaking monumental task that required a great deal of patience. The question that ran through my mind constantly was, “What are the Spanish Archives of Laredo doing at St. Mary’s University?”

I had no earthly idea that there existed a wealth of historical information about my hometown. The only inkling I had of Laredo’s Spanish history was Don José de Escandón’s red granite historical marker on the northeast side of historic San Agustín Plaza, commemorating the site of the original Villa de San Agustín de Laredo. I would see this marker almost on a daily basis since the plaza was located across the street from St. Augustine School.

I got the job.

Every afternoon, I looked forward to handling the actual Spanish documents with vinyl gloves. Some of them were too fragile, badly frayed, or almost illegible to read. The Special Collections Room was big enough to accommodate a few tables, and that is where we worked.

The documents were kept inside a walk-in steel vault in a heavy four-drawer steel filing cabinet, which was kept locked at all times. The vault door had a lock, and Miss Perry was the only one who knew the combination.

Each document was kept in a separate Lancaster bond folder. I found out from Miss Perry that these were the conditions that were stipulated in the agreement on December 10, 1961, when the University formally accepted custodianship of the Spanish Archives of Laredo.

We would take one document at a time, study it, and fill in the information on a 5×8 index card. On the upper left hand side, we filled Provence and Destination. On the upper right hand, we filled in the box number relative to the document and the date. Then, we filled in the FROM and TO of the document, the type of communication, and the condition of the document.

And, finally we wrote a brief description of the content. The cards were then cross-referenced with numerous sources so that a researcher could quickly find a document dealing with a specific subject. There were 3,245 separate documents for a total of 13, 343 pages. The oldest document was dated 1749, and the most recent one was from 1868.

-JGQ