As I continue day to pray every day for the victims of the horrific floods caused by Hurricane Harvey and remember those who perished, I cannot help but sympathize and empathize with what those poor people are going through. It was 63 years ago in the summer of 1954 that Laredo experienced one of its worst floods in history.

During the latter part of June 1954, heavy thunderstorms fell on the city for several days. One afternoon Papá, my older brother Peter, and I walked down three blocks south on San Pablo Avenue to the Río Grande. Papá wanted to show us how high the river was cresting. Evidently, news of this event had spread throughout the Barrio El Azteca because we saw many people there who were just standing on the banks staring at the rising currents.

Then a few days later, a major catastrophe occurred on Monday the 28th. Mamá heard on the radio that an enormous hurricane named Alice was going to strike close by and flood the river, much worse than what it already was.

She kept listening for daily bulletins. Don Basilio Gutiérrez, the owner of our rented house at 402 San Pablo Avenue, came by to tell her that we might need to evacuate and move to higher ground. Carlos the barber, Conchita Salazar, Miss Chapa, Doña Visitación Cantú, my grandmother Memia, and Doña Gloria Lozano all stopped by the house to tell Mamá the latest news. It seemed from all the commotion I was hearing that the families and businesses on San Pablo Avenue were greatly concerned about the flooding and its impact on the Arroyo El Zacate. Neighbors were visiting each other in a state of frenzy. I watched all this action from the concrete step in front of the house. I had never seen a flood before and had no idea what to expect.

On Tuesday morning, June 29, the river was cresting at 42.04 feet and rising at the rate of three feet per hour and flowing over the International Bridge. Don Basilio, who was also my godfather for my First Holy Communion, stopped by to let Mamá know that the Arroyo El Zacate was going to be flooded and that we better move out.

After lunch, I was startled by the big loudspeaker atop a police car blaring out warnings in Spanish, telling the residents of the flooding on the river. Mamá kept reassuring us not to worry, that the waters from the creek would not reach our house. Peter, my older sister Lupe, and I believed her and felt safe. Like Papá, my grandfather Pana was also at work.

By late afternoon, the Arroyo El Zacate had flooded San Pablo Avenue and the water had reached the concrete step where I had sat a day before. Mamá was panicking now and Peter, Lupe, and I were on the verge of tears. We were scared. She did not want to leave because we had no place to go. I kept saying to myself, “What are we going to do?”

I looked at Mamá and saw fear written all over her face. I knew right then the meaning of this strong emotion. There was a strange stillness in the neighborhood. I did not hear people talking or walking, or the traffic noise. It felt as though everyone had abandoned us. Doña Gloria told Mamá that she and her husband were not going to stay upstairs in their apartment. It was only the four of us, and we had not seen or heard from Papá, Memia, or Pana.

Suddenly, a loud bass voice in Spanish boomed through the screen door and broke the silence. Mamá was kneeling in front of her little altar praying to Our Lady of Guadalupe. A man in a uniform, along with two other soldiers appeared in a big boat. Papá later told me that the men were members of the National Guard and the amphibious vehicle was designed to rescue people.

Mamá still did not want to leave. A soldier ordered Peter, Lupe, and me to get in the boat, which by now was anchored right by the front door. We obeyed without hesitation. They grabbed us by the waist and placed us safely inside. Two of them went back and picked up Mamá and carried her to the boat. I was still scared, but I felt safe. I glanced down on San Pablo Avenue towards the house where Doña Luisa made her fresh and delicious corn tortillas, towards the house where the wake had taken place, towards the house where I was born, towards the house where Don Julio Campos and his wife Doña Visitación and their two daughters lived, and all the houses were underwater.

As we started moving forward, my eyes met the big two-story brick house of Conchita Salazar and Miss Chapa. The water had flooded the basement and was quickly rising. I wondered if the two women were up on the second floor by themselves.

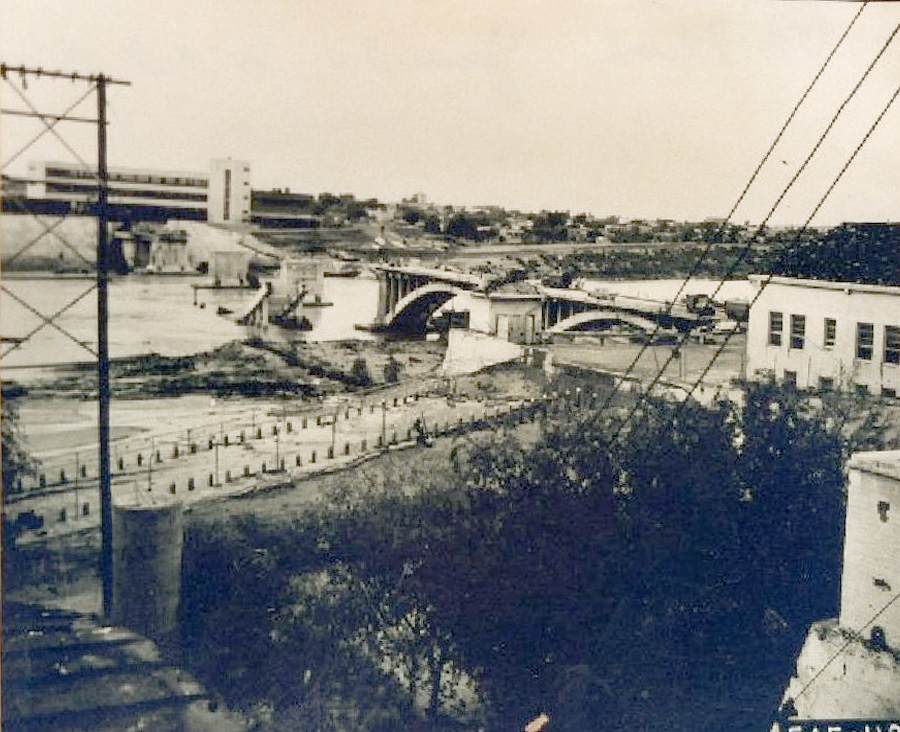

When the boat turned right at the corner of San Pablo Avenue and Iturbide Street, I turned my head to the left and saw that the Arroyo El Zacate Bridge where I had stuck my head one day through one of the elongated and narrow arches had completely disappeared. It was now one big lake. We continued going right, and then went across the street to Don Basilio Gutiérrez’s gasoline station and stopped by the edge of the water. Pana and Memia’s small framed house looked abandoned. We were ordered out and one of the soldiers took us next door to the two-story white stone house that belonged to the Ruiz family. He told us we would be safe there.

We ascended the creaking exterior wooden staircase and entered a big room that had little furniture and no beds. Pana and Memia were sitting on two small wooden chairs and got up to greet us. The Ruiz family was there, too, making us feel at home. Their two daughters, Stella and Sylvia came over to join Peter, Lupe, and me. Their mother was holding baby Teresita.

The windows did not have curtains, and I could see that it was dark already. I had no idea what time it was, but I do remember that Papá walked in some time later. He was still wearing his bus driver’s light grey uniform. He worked for the Laredo Transportation Company. The sides of the pants had a black stripe, about an inch wide, running lengthwise. He explained to Mamá and to the group that since the Arroyo El Zacate Bridge was closed, he was given another route. I was too tired from all the excitement. The lights were turned off and we all fell asleep on the cold linoleum floor.

A crashing knock at the door woke me up from a deep sleep. We were all in a state of somnambulism. Somebody managed to turn on the lights while Don Ruiz opened the door. The National Guard soldier with the loud bass voice told him that we had to leave because the water was getting close to the first floor. He said that there was no time to waste. Papá looked at his watch and said it was after midnight. We all went outside and waited while three soldiers spoke to the adults and pointed west.

Leaving them behind, we started walking in the middle of Iturbide Street. There was not a car in sight. Mamá was holding Lupe’s hand and mine. Peter was walking with Papá and Pana and Memia. People started getting out of their houses and joining us. I had no idea where we were going.

After walking for five blocks, we turned right on San Eduardo Avenue and then immediately to our left were some open empty rooms that were part of a long one story building. Some more National Guard soldiers were standing outside and motioning us to enter. Papá, Mamá, Pana, Memia, and the three of us went in and lay on the cold stone floor. The rest of the people went into other rooms. We slept through the night.

I had not brought any of my toys or books with me. I did not have time to think about them or anything else. All we could salvage was the clothes on our backs. Early the next morning, someone from the Red Cross knocked at the door and brought us cold milk, beef tacos, and coffee for the grownups. Our room contained a bathroom with a flushing toilet and a sink. I was so grateful we didn’t have to use a chamber pot. We were completely safe because the flood did not reach this far. After breakfast we walked down Iturbide Street one block to San Francisco Avenue to watch the National Guard soldiers patrol the streets by boat.

I found out by listening to Pana and Papá talking that this place belonged to la Señora María Bertani, a very wealthy woman who reportedly owned half of the city of Laredo. She lived by herself in a huge two-story frame house on Iturbide Street and around the corner from where we were staying. It had a big garden in the front that resembled a park, and a wrought iron fence higher than my head surrounded the property. Pana was telling Papá that he was her gardener on weekends. I often heard the loudspeaker from a patrol car coming by very slowly, telling us in Spanish to bring containers and to go to a certain location and receive clean drinking water. To get something to eat, Papá was told to take the family to Central Elementary School (La Escuela Amarilla), a distance of five blocks, where the Red Cross was providing food.

That afternoon I borrowed the Laredo newspaper that somebody had given Papá. It was dated June 30, 1954, and the headlines read: ”Rio Grande Starts Dropping, Big Flood Crests At 62 Feet,” and the article started with, “Thousands Left Homeless; Sister Cities Isolated.” According to the story, this inundation was the biggest on record, “which left thousands in the Laredo-Nuevo Laredo area homeless, virtually isolating the sister cities and doing untold damage …”

This confirmed what the grownups were talking about, the destruction to houses on both sides of the creek. I ran to Mamá to ask her if our house was still there. She said she did not know. I also heard Papá saying that the International Bridge had been destroyed. Now, there was no way to go across to the Mexican side and find out what happened to our aunt Mamatay and her husband Don Manuel Ibarra, and Father Tomás Lozano.

Every day we went to Central Elementary School to receive our ration of food and drinking water from the Red Cross. For about a week, I did not take a bath, nobody did.

Papá went to see what he could salvage from our house and told us that he had to take off his shoes and socks because the water was knee deep. One day we all walked so many blocks that I lost count. We were told to go to this huge building that was Martin High School. Inside the big gymnasium, there were hundreds of people, all moving rather slowly in several queues. We got behind one and I heard children crying up ahead where men and women in white coats were giving typhoid inoculations.

A National Guard soldier knocked at our door one afternoon and told Papá that the waters had completely receded and that it was safe for us to return to our home. It had seemed like an eternity that we had been gone. We all had a big smile and a happy face. The sky was sunny and cloudless when we hurriedly and anxiously walked back. I noticed some cars moving in both directions on Iturbide Street which meant that thru traffic across the Arroyo El Zacate Bridge was now open. We left Pana and Memia at their house and noticed that Don Basilio and his family were back home busy cleaning the floors, and so was the Ruiz family. Their pet dog Spot was with them and came running when he saw me. When Mamá opened the wooden front door, the sunlight hit us and we knew something was terribly wrong.

A big part of the west wall had fallen. Chunks of bricks with mortar were all over the two small beds and the roll away bed and they were bunched in one corner of the room under a foot of stinking mud. Only a sliver of wall remained miraculously holding the framed picture of Our Lady of Guadalupe and Mamá’s little altar. All our clothing was gone, as was the chamber pot. The few pieces of furniture were completely ruined. In other words, we did not have a home anymore. The house looked like a bomb had hit it. Poor Mamá uttered a loud scream and then started crying in front of the venerable icon. I did not see any of my books or toys. We had lost everything. Those wonderful memories were all I had left. Her oil lamp was on the floor covered with mire. The musty, stale and putrid stench emanating from the remaining walls and the floor was unbearable.

Papá went to see his parents, Pana and Memia, while Peter, Lupe, and I stood next to Mamá and prayed silently. My only plea to Jesus, my Lord and Savior, was why? I also asked Him to help our parents.

Papá came back and told us that we were going to stay with our grandparents for a few days until we could find another house. We did not have a choice. He was not working, so Pana helped us financially by buying groceries. In the meantime, Papá came down with an infection on his feet and was totally incapacitated. Dr. Raúl de la Garza said that he had contracted a serious bacterial agent by walking barefoot in the dirty waters when he went to check on the house and that unknowingly, the contamination set in through minor cuts. He gave Mamá a prescription to take to the pharmacy. I went with Pana and he paid for the medications. Two days later, he came home after work and told us he had found a house for rent at 210 Iturbide Street, one and a half blocks away.

The old frame house where I was born at the northwest corner of San Pablo Avenue and Lincoln Street is still there. We lived in this house from 1945 until 1950. The streets were not paved then. From there we had moved up the street to 402 San Pablo, close to the corner with Iturbide Street (directly across from where the police substation is now located. The house now looks dilapidated and abandoned. It is all boarded up.

When we were living there Mamá made sure we had a “home,” with lots of affection. love, care, and compassion and three complete meals every day. Our home was filled with God’s love, mercy, and blessings, and we never uttered a complaint. We always had new clothing and new shoes. She made sure we took a bath every night and brushed our teeth before going to bed. The house had only two rooms, the kitchen and dining room were together in one room and the other room was for the two beds and a roll away bed. We had no running water except in the kitchen. Since we lived across the Arroyo El Zacate, I remember two instances when we encountered rattlesnakes inside the house!

(J. Gilberto Quezada is a retired public school administrator, an award-winning author, writer, novelist, essayist, and poet. His political biography, Border Boss: Manuel B. Bravo and Zapata County, published by Texas A&M University Press in 1999 received the prestigious Texas Institute of Letters Award, the Webb County Heritage Foundation Award, and the American Association for State and Local History Award.)